It was thrilling to see that the definition of “meaningful broadband adoption” from my 2016 Benton Foundation report appeared in the final version of H.R. 3684, the “Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act.” This bill was passed by Congress and signed into law by President Biden on November 15, 2021. There are many people to thank and share credit with this success, including those who helped to deepen my own knowledge about and expand previous, more conservative definitions of broadband adoption. In the space below, I will share a bit more detail about how this language and understanding developed.

It was thrilling to see that the definition of “meaningful broadband adoption” from my 2016 Benton Foundation report appeared in the final version of H.R. 3684, the “Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act.” This bill was passed by Congress and signed into law by President Biden on November 15, 2021. There are many people to thank and share credit with this success, including those who helped to deepen my own knowledge about and expand previous, more conservative definitions of broadband adoption. In the space below, I will share a bit more detail about how this language and understanding developed.

The credit begins over 10 years ago with my colleagues, Seeta Peña Gangadharan (London School of Economics) and Greta Byrum (Social Science Research Council) who were both employed at the New America Foundation’s Open Technology Institute (OTI) at the time. In 2011, while I was a doctoral student in the Graduate School of Library and Information Science at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, I was selected to join OTI as a Google Policy Fellow. I spent 10 weeks during the summer in Washington, D.C. learning from and working with both Seeta and Greta, as well as many others inside the beltway.

During my time at OTI that summer and into the following year, I worked on a research project funded by the Knight Foundation to evaluate the Free Library of Philadelphia’s Hot Spots program. In a paper that I wrote about the research, I described the program in this way:

The Free Library Hot Spots are public computing facilities embedded within four community-based organizations located in North, South, and West Philadelphia, where several hundred thousand people lack access to the Internet at home (The Pew Charitable Trusts’ Philadelphia Research Initiative, 2012, p. 5). The Hot Spots are funded by a 2-year grant from the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. The project has four objectives: (1) to increase access to computers and the Internet for individuals in underserved neighborhoods throughout Philadelphia; (2) to increase computer literacy and access to training; (3) to increase understanding of and comfort with computers and the Internet; and (4) to increase awareness of Free Library services and materials.

One of the most significant things that I learned during this experience was how the Free Library Hot Spots helped people to adopt broadband outside of the home in community centers, including churches and community-based organizations. This happened in large part, as I argued, because the Hot Spots helped people to develop a sense of comfort as a precursor to their broadband access. By sense of comfort, I meant that people who worked inside the Free Library Hot Spots helped other people, in some cases their neighbors, in low-income communities in Philadelphia to gain the support, trust, safety, and respect from those working with them. These social aspects of internet use in public spaces had certainly been identified in previous studies, as I wrote about in my paper. However, these social and community contexts had not yet been as clearly articulated necessarily in the context of broadband adoption as a federal policy goal. As I described in the paper,

One of the most significant things that I learned during this experience was how the Free Library Hot Spots helped people to adopt broadband outside of the home in community centers, including churches and community-based organizations. This happened in large part, as I argued, because the Hot Spots helped people to develop a sense of comfort as a precursor to their broadband access. By sense of comfort, I meant that people who worked inside the Free Library Hot Spots helped other people, in some cases their neighbors, in low-income communities in Philadelphia to gain the support, trust, safety, and respect from those working with them. These social aspects of internet use in public spaces had certainly been identified in previous studies, as I wrote about in my paper. However, these social and community contexts had not yet been as clearly articulated necessarily in the context of broadband adoption as a federal policy goal. As I described in the paper,

This broadband adoption literature, like the digital divide studies before it, has been largely defined and measured by Internet access and use at home. The approach is a practical one, based on data gathered through the U.S. census. However, recent federal initiatives have helped shift the policy focus. The NTIA, Rural Utilities Service, Institute for Museum and Library Services, and other U.S. government agencies and civil society groups have recognized that Internet access at home is only one way to measure broadband adoption.

By showing that the Free Library Hot Spots, like many other public computing initiatives before them, had played a critical role in helping new and existing internet users learn how to adopt broadband in public spaces outside the home, the need to incorporate more social, community, and ecological definitions of broadband grew in momentum and importance in digital inclusion research, practice, and policy at this time.

It is thanks to Seeta and Greta, particularly in their convening of scholars, policymakers, and practitioners who participated in the April 2012 Defining and Measuring Meaningful Broadband Adoption event at the New America Foundation that helped set the stage and lay the groundwork for a new way of understanding and articulating broadband adoption. The papers presented at the event in April culminated in a special issue of the International Journal of Communication, which was also published in 2012. In Seeta and Greta’s introduction to the special issue, they added a key contribution to the broadband adoption literature through their definition of “meaningful broadband adoption,” which is described in the following paragraphs:

We call this approach to digital inclusion research the study of meaningful broadband adoption, by which we mean the systematic observation and analysis of the social layer of broadband access. This social layer depends upon an individual’s interaction with his or her community, which in turn helps shape the degree of relevance of broadband technologies to his or her life. The social context may determine levels of comfort and satisfaction as well as the context for use of broadband technologies, including place of access (home, public or community institution, work) and modality (wireless or wired).

Thus, when we talk about meaningful broadband adoption, we imply an ecology of support—institutions, organizations, and even informal groups that serve to welcome new users into broadband worlds; share social norms, practices, and processes related to using these technologies; and help policy targets make sense of and exercise control over how broadband enters users’ lives. Meaningful broadband adoption thus refers to a range of broadband-related activities and experiences that target populations and their supporters construct, and often define, for themselves. We also imply a rigorous research agenda that explores a range of outcome variables as well as a range of independent variables.

This experience of researching the Free Library Hot Spots, participating in the event at New America, and publishing my first academic journal article as a result, is all thanks to Seeta and Greta’s support as well as several others who I thanked in the acknowledgement section of my paper in the special issue. I later learned that this experience would have a significant impact on helping to shape federal broadband policy in the years to come.

In 2015, I had the extraordinary opportunity to become a Faculty Research Fellow with the Benton Foundation to conduct a study of digital inclusion programs in communities across the U.S. For this opportunity, I am grateful to Angela Siefer (National Digital Inclusion Alliance) and Amina Fazlullah (Common Sense Media) who introduced me to Adrianne Furniss, Executive Director of the Benton Foundation. During this time, the Federal Communications Commission was working to reform the Lifeline Program to become a program that provided a broadband subsidy for qualifying low-income consumers. This was a huge deal at the end of the Obama Administration, because the Lifeline program for years (since the Reagan Administration) had only focused on helping low-income individuals gain access to telephone service. For those working with low-income individuals and families to adopt broadband this was an exciting development that could have a huge impact on addressing the digital divide.

In 2015, I had the extraordinary opportunity to become a Faculty Research Fellow with the Benton Foundation to conduct a study of digital inclusion programs in communities across the U.S. For this opportunity, I am grateful to Angela Siefer (National Digital Inclusion Alliance) and Amina Fazlullah (Common Sense Media) who introduced me to Adrianne Furniss, Executive Director of the Benton Foundation. During this time, the Federal Communications Commission was working to reform the Lifeline Program to become a program that provided a broadband subsidy for qualifying low-income consumers. This was a huge deal at the end of the Obama Administration, because the Lifeline program for years (since the Reagan Administration) had only focused on helping low-income individuals gain access to telephone service. For those working with low-income individuals and families to adopt broadband this was an exciting development that could have a huge impact on addressing the digital divide.

As part of the study, I was particularly interested to know what else besides low-cost internet opportunities and digital literacy training were important for policymakers to consider as the FCC worked to reform the Lifeline program. In other words, if the FCC was going to help make low-cost internet more accessible to low-income individuals and families across the country, what else should federal policymakers be aware of in efforts to promote broadband adoption?

The findings from my research were published in a 2016 report for the Benton Foundation, titled “Digital Inclusion and Meaningful Broadband Adoption Initiatives.” And, it’s the definition of broadband adoption in the report that made it into H.R. 3684, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act.

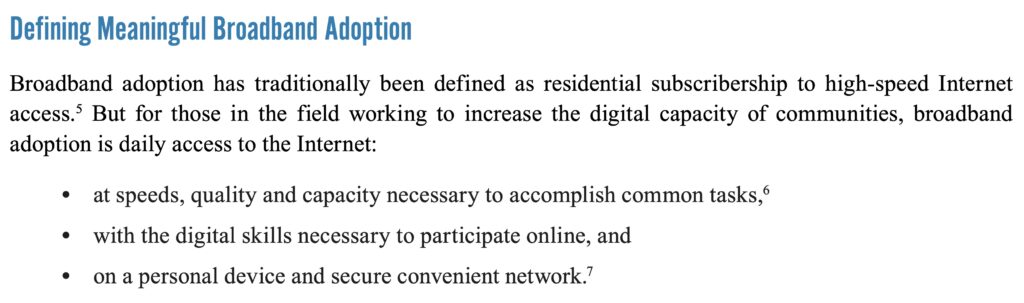

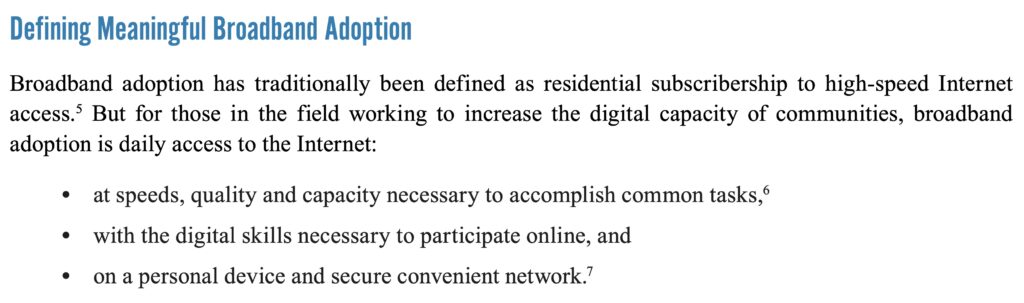

Here is the definition of broadband adoption which is found on page 8 in my report for the Benton Foundation:

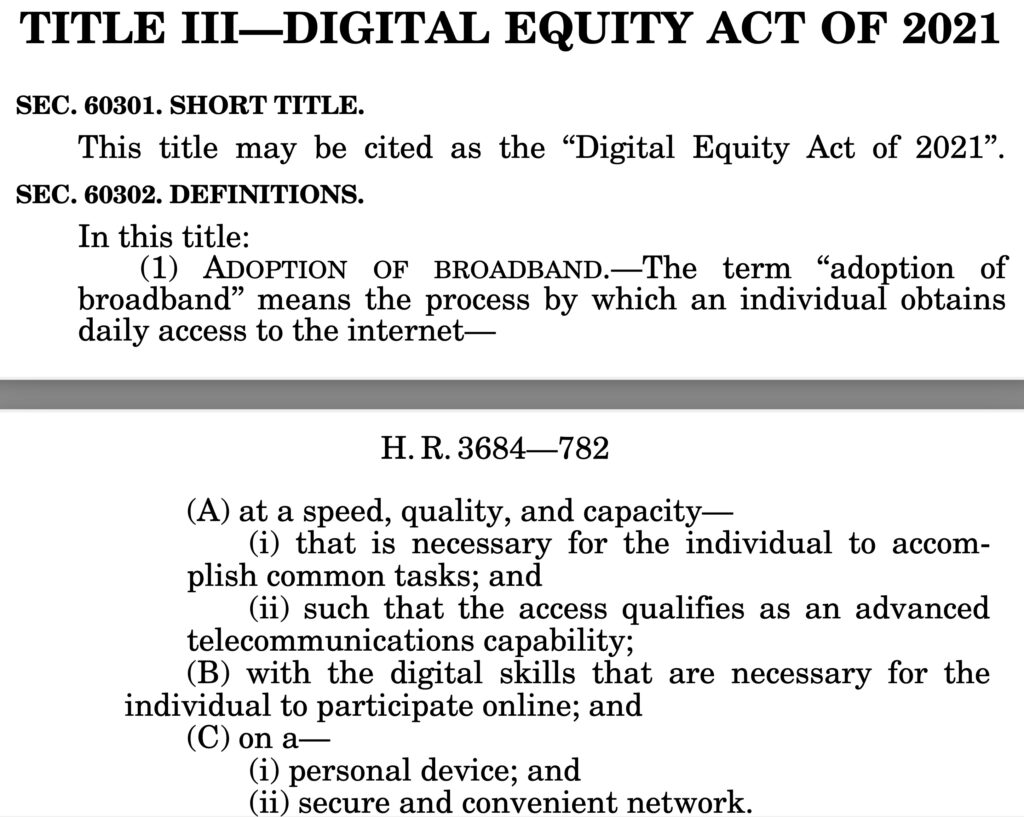

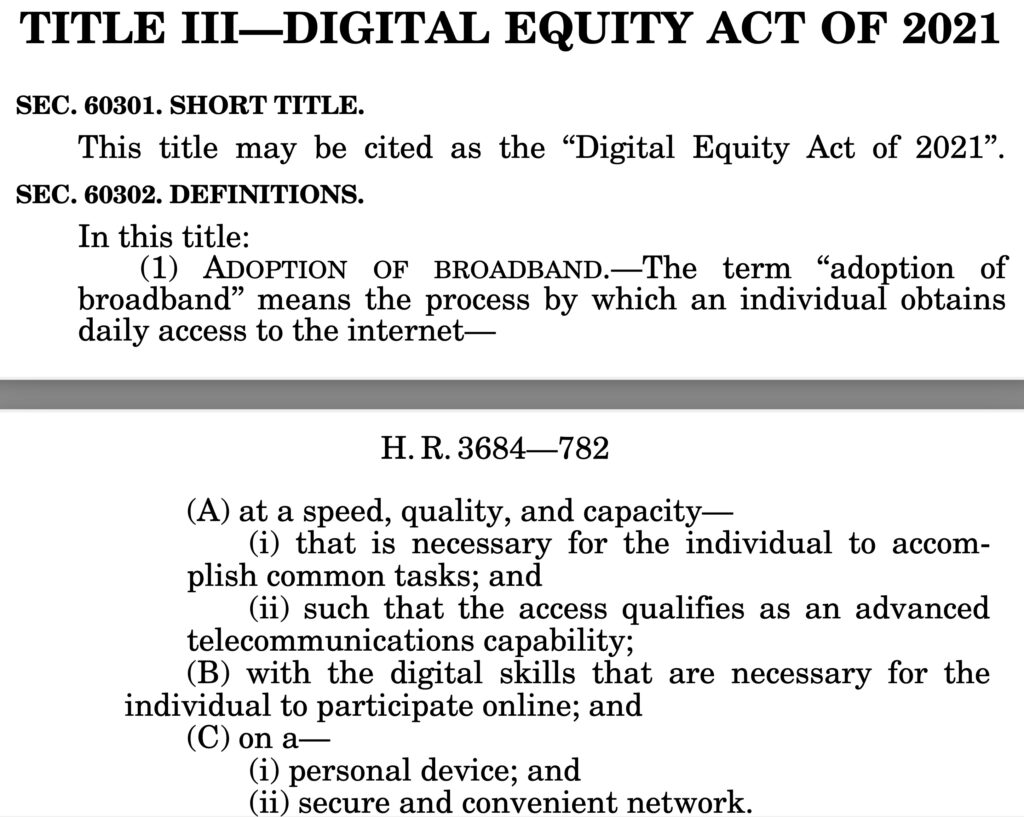

Here is the definition titled “adoption of broadband,” which can be found in the final version of H.R. 3684 on pages 781 & 782:

As these examples show, the two definitions are almost identical. It is also not entirely surprising however that the definition from the Benton report made it into H.R. 3684. This is because the definition of meaningful broadband adoption in my 2016 report was added to the Definitions page on the National Digital Inclusion Alliance website. The NDIA also played a critical role in the development of both the definition itself as well as the Digital Equity Act of 2021. Therefore, I am grateful to Angela Siefer and NDIA, as well as the Benton Institute for Broadband & Society, where I am currently the Senior Director of Research and Fellowships, for sharing my work on digital inclusion and broadband adoption toward this goal.

In 2022, there is still much more work that needs to be done to assist people in adopting broadband inside and outside the home. With the passing of H.R. 3684 and recent efforts to promote digital equity in states across the nation, there is even more urgency and need to embrace social, community, and ecological approaches to broadband adoption and digital equity in the months and years ahead. This is why I also believe that gaining a deeper understanding of the role and impact that digital inclusion coalitions play in promoting what I am calling digital equity ecosystems is critical toward this goal.

As states across the U.S. develop their digital equity plans this year, as part of the National Telecommunications and Information Administration’s BEAD and DEA grant programs, a comprehensive and holistic framework is needed to evaluate the outcomes and impacts of these federal investments to advance digital equity in the years to come.

As states across the U.S. develop their digital equity plans this year, as part of the National Telecommunications and Information Administration’s BEAD and DEA grant programs, a comprehensive and holistic framework is needed to evaluate the outcomes and impacts of these federal investments to advance digital equity in the years to come.